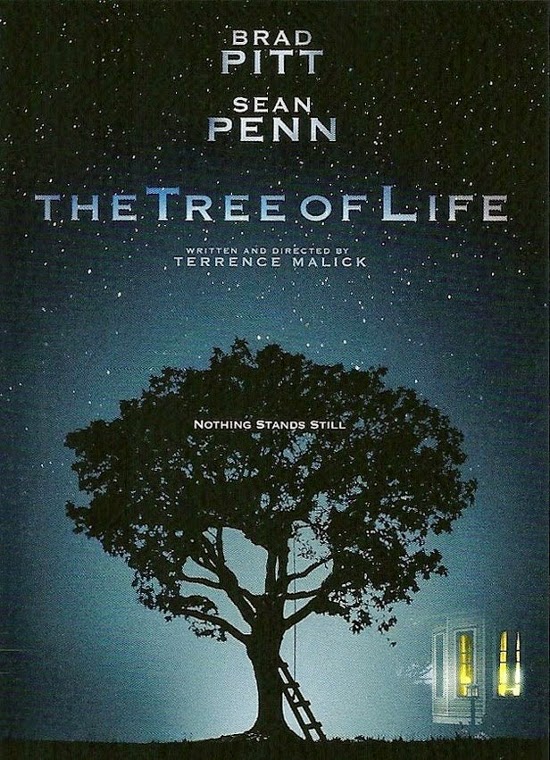

Talking about The Tree of Life is almost impossible without immediately descending into the realm of subjective opinion. It is so uniquely idiosyncratic that you can't compare it to anything else in objective terms. I could tell you that I think it's one of the greatest films ever made, but for somebody already skeptical of critical objectivity I have no way to back up that claim. I know there are many people who hate it, and they're not wrong to do so. I have no cards to play; there's nothing for me to do but tip my hand.

I loved it.

I didn't love all of it the same amount or the same way, though. There were moments when I thought it had the potential to be one my favorite movies of all time, but there were also moments when I thought it wasn't even my favorite Malick (a question I'm still torn on, actually). At times it is boldly abstract (rewinding to the beginning of time), and this is where my affection for it is strongest. Then at other times it is firmly grounded in plot and character, and here I found myself longing for the more metaphysical side of the film.

But while the beauty of Malick's impressionism left me wishing for more, much of what I love about him as a director is his ability to use concrete narrative to convey thematic ideas. He uses grounded storytelling to reach back toward the abstract. Here his explicit central concern is with the distinction between nature (embodied in Brad Pitt's character) and grace (embodied in Jessica Chastain's), which he essentially defines (in Chastain's voiceover) as selfishness and selflessness, though the words obviously have further connotations.

The same voiceover continues, "The nuns taught us that no one who loves the way of grace ever comes to a bad end," so it would be reasonable to assume that the film is telling us to side with grace over nature. Brad Pitt is often very hard on his kids, and there are moments where they seem to love Jessica Chastain more than him. The issue is never this black and white, however, and I think it makes more sense to read this as Chastain's character rather than the voice of the director coming through the film. As much as Pitt may be hard on his family, they fall apart without him.

But this is only the discussion happening on the surface of the text. This is how Malick is telling us to read his story, but it's not the only way that it can be read. Beyond the explicit meanings, there are also implicit ones as well.

If you look merely at the surface of Malick's films, he may seem to prioritize the beauty of nature over the sterility of society, but in all his work he has been concerned with the "war in the heart of nature," with the idea that there is "no cosmic power, only action of hands upon the world." This might seem like a strange thesis for a man who includes a magnificent sequence of the birth of the universe (the origin of cosmic power), but it's important to note that he ends this sequence with a moment of pure contingency: a meteor striking Earth and destroying everything which this supposed "cosmic power" had created.

And this conflict between "cosmic power" and "hands upon the world" continues to play out beyond the birth of the universe sequence. God is also framed as a cosmic power whose influence over Earthly events comes into question ("He is in God's hands now" / "He was in God's hands the whole time."). The religious side of the film is concerned primarily with the book of Job and the questions of whether we are punished in order to prove our fortitude and of whether the cost of our sacrifice is worth the solace of our belief.

On top of this dialogue there's also a visual contrast played out between nature (as the environment, not necessarily as "human nature") and society (in its artificial, inhuman aspects). Brad Pitt and his family live in a rural area, while Sean Penn (his now-grown son) lives alone in an urban, industrialized landscape. Again, the obvious temptation is to assume that the countryside is praised as greater than the the city, but the buildings and bridges of the metropolitan frontier are presented with just as much majesty as the forests of the rustic society, and there's just as much (if not more) tragedy in the more "natural" setting.

In psychoanalytic terms, Malick seems to be yearning for a fantasmatic, presymbolic space (particularly with the opening quote from Job: "Where were you when I laid the foundations of the Earth?"). His films always feel like they're laced with a hint of nostalgia, as if he wishes to return to a better time before everything was so evil. But at the same time, he also interrogates this yearning and this idea of a perfect, mythical past, and he shows that the good and the bad were always already contained within the same moment (e.g. the hand at the end of the film which is old and then young, as if age and youth were contained within the same body).

The Tree of Life really swept me off my feet. There was one moment that missed its mark for me ("God lives up there!"), and generally I thought the voiceover in The Thin Red Line was more effective, but for the most part I was in a constant state of awe. Its first act is like the final act of 2001 in a big way, and by beginning with a trip Beyond the Infinite (or perhaps Before the Infinite), I immediately knew I was in for something special. Even after this opening, the movie is absolutely filled with haunting imagery. The idea of writing about everything in it on a single viewing is just absurd, but I hope this gives you a good idea of what was going through my mind and of what kind of movie you're in for if you decide to experience it for yourself. I doubt very much that this will be my last time talking about this incredible film. Until then, here's an alternate review I drafted up before I decided to try and write something real (warning–I'm not very funny):

[Selling the concept to the studio]

"We'll get the best photographer on the planet, give him our most expensive cameras, and tell him to go take pictures of lots of boring nature stuff. You know, National Geographic-style. Then, just as the audience is getting ready for another New World—BAM!—we'll throw in some outer space and dinosaurs and stuff. The fans will eat it right up, and the critics will have a blast tearing it apart. Win-win."

"Alright, but we have to get Sean Penn and have him wander around the desert for no reason."

"Deal."

Related Lists

Favorites by Director | Best Picture Losers

Terrence Malick | Emmanuel Lubezki

My Rewatch List

I loved it.

I didn't love all of it the same amount or the same way, though. There were moments when I thought it had the potential to be one my favorite movies of all time, but there were also moments when I thought it wasn't even my favorite Malick (a question I'm still torn on, actually). At times it is boldly abstract (rewinding to the beginning of time), and this is where my affection for it is strongest. Then at other times it is firmly grounded in plot and character, and here I found myself longing for the more metaphysical side of the film.

But while the beauty of Malick's impressionism left me wishing for more, much of what I love about him as a director is his ability to use concrete narrative to convey thematic ideas. He uses grounded storytelling to reach back toward the abstract. Here his explicit central concern is with the distinction between nature (embodied in Brad Pitt's character) and grace (embodied in Jessica Chastain's), which he essentially defines (in Chastain's voiceover) as selfishness and selflessness, though the words obviously have further connotations.

The same voiceover continues, "The nuns taught us that no one who loves the way of grace ever comes to a bad end," so it would be reasonable to assume that the film is telling us to side with grace over nature. Brad Pitt is often very hard on his kids, and there are moments where they seem to love Jessica Chastain more than him. The issue is never this black and white, however, and I think it makes more sense to read this as Chastain's character rather than the voice of the director coming through the film. As much as Pitt may be hard on his family, they fall apart without him.

But this is only the discussion happening on the surface of the text. This is how Malick is telling us to read his story, but it's not the only way that it can be read. Beyond the explicit meanings, there are also implicit ones as well.

If you look merely at the surface of Malick's films, he may seem to prioritize the beauty of nature over the sterility of society, but in all his work he has been concerned with the "war in the heart of nature," with the idea that there is "no cosmic power, only action of hands upon the world." This might seem like a strange thesis for a man who includes a magnificent sequence of the birth of the universe (the origin of cosmic power), but it's important to note that he ends this sequence with a moment of pure contingency: a meteor striking Earth and destroying everything which this supposed "cosmic power" had created.

And this conflict between "cosmic power" and "hands upon the world" continues to play out beyond the birth of the universe sequence. God is also framed as a cosmic power whose influence over Earthly events comes into question ("He is in God's hands now" / "He was in God's hands the whole time."). The religious side of the film is concerned primarily with the book of Job and the questions of whether we are punished in order to prove our fortitude and of whether the cost of our sacrifice is worth the solace of our belief.

On top of this dialogue there's also a visual contrast played out between nature (as the environment, not necessarily as "human nature") and society (in its artificial, inhuman aspects). Brad Pitt and his family live in a rural area, while Sean Penn (his now-grown son) lives alone in an urban, industrialized landscape. Again, the obvious temptation is to assume that the countryside is praised as greater than the the city, but the buildings and bridges of the metropolitan frontier are presented with just as much majesty as the forests of the rustic society, and there's just as much (if not more) tragedy in the more "natural" setting.

In psychoanalytic terms, Malick seems to be yearning for a fantasmatic, presymbolic space (particularly with the opening quote from Job: "Where were you when I laid the foundations of the Earth?"). His films always feel like they're laced with a hint of nostalgia, as if he wishes to return to a better time before everything was so evil. But at the same time, he also interrogates this yearning and this idea of a perfect, mythical past, and he shows that the good and the bad were always already contained within the same moment (e.g. the hand at the end of the film which is old and then young, as if age and youth were contained within the same body).

The Tree of Life really swept me off my feet. There was one moment that missed its mark for me ("God lives up there!"), and generally I thought the voiceover in The Thin Red Line was more effective, but for the most part I was in a constant state of awe. Its first act is like the final act of 2001 in a big way, and by beginning with a trip Beyond the Infinite (or perhaps Before the Infinite), I immediately knew I was in for something special. Even after this opening, the movie is absolutely filled with haunting imagery. The idea of writing about everything in it on a single viewing is just absurd, but I hope this gives you a good idea of what was going through my mind and of what kind of movie you're in for if you decide to experience it for yourself. I doubt very much that this will be my last time talking about this incredible film. Until then, here's an alternate review I drafted up before I decided to try and write something real (warning–I'm not very funny):

[Selling the concept to the studio]

"We'll get the best photographer on the planet, give him our most expensive cameras, and tell him to go take pictures of lots of boring nature stuff. You know, National Geographic-style. Then, just as the audience is getting ready for another New World—BAM!—we'll throw in some outer space and dinosaurs and stuff. The fans will eat it right up, and the critics will have a blast tearing it apart. Win-win."

"Alright, but we have to get Sean Penn and have him wander around the desert for no reason."

"Deal."

Related Lists

Favorites by Director | Best Picture Losers

Terrence Malick | Emmanuel Lubezki

My Rewatch List

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment